When planning where you want your portfolio to be 10–20 years from now, the goal is usually to build a corpus that generates sustainable income. Many investors accumulate shares in companies like ITC Limited, Coal India, Indian Oil, and Vedanta Limited—well known for their attractive dividend yields. This reflects a preference for income investing, where regular cash flow is prioritised over capital growth.

But is dividend the optimal strategy for long-term wealth creation, or could growth-focused investing offer better outcomes?

People prefer it because they get a certain cash flow without selling their shares and reducing their holdings. However, it can hamper their long-term growth.

Why do dividends hamper long-term growth?

For most retail investors, dividends are often small and challenging to reinvest effectively in the stock market—especially in India, where Dividend Reinvestment Plans (DRIPs) aren’t widely available. As a result, these payouts often get absorbed into day-to-day expenses, disrupting the power of compounding that could have worked on retained earnings.

How does it hamper future growth? Let’s take a small example.

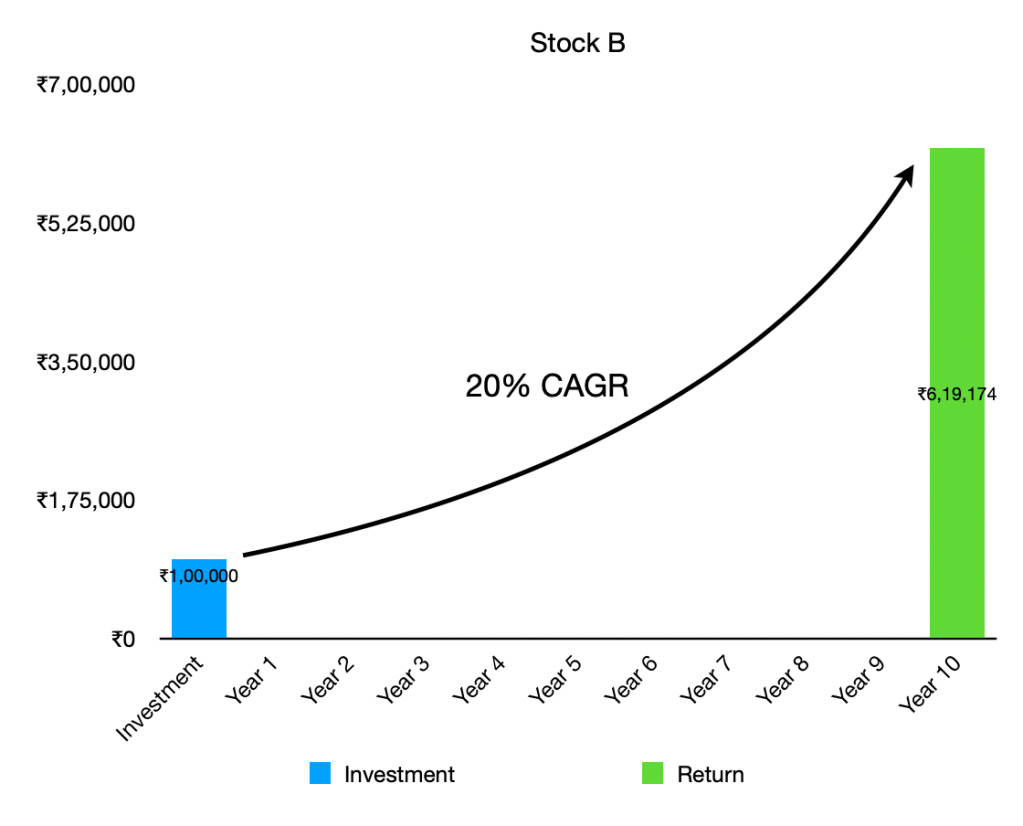

There are 2 stocks: Stock A and Stock B. Both gave 20% CAGR over 10 years, but Stock A has a 5% dividend yield while Stock B reinvests its profits back into the business.

Suppose you invested ₹1 lakh in both stocks. Let’s see what happens to your cash flow:

The return in both cases is the same—20% CAGR—but the purpose of investment is to create a corpus in the future that can be used to fund retirement or planned expenses. With dividends, the investor just received ₹6,000 in Year 1 to ₹17,116 in Year 9. Considering the investor made an investment of ₹1 lakh in a stock, this amount is not enough to make a considerable investment, hence it often gets used up in daily life.

Meanwhile, the stock that reinvested its profit provided nearly 60% more corpus—₹6,19,174 compared to ₹3,90,234. Thus, the dividend didn’t really help in this case.

This difference is largely because retained earnings allow companies to reinvest in R&D, expand operations, and capture new markets—resulting in higher share price appreciation over time. (However, in the above case, we took the growth rate same in both the cases) Retained earnings, being the cheapest source of capital, offer good growth opportunities to company.

Would dividends be a good income?

For large portfolios (₹10 crore), even a modest 1% dividend yield translates to ₹10 lakh annually—a meaningful income stream for retirement. However, investors could also consider Systematic Withdrawal Plans (SWPs), where they systematically sell a portion of their holdings. This approach provides more control, allowing flexibility to withdraw more in years of high expenses and less in others, unlike fixed dividends.

Yes, it can work, but is dividend really the right choice from a financial planning point of view?

There is another way to earn such an income: you could sell ₹10 lakh worth of shares every year (₹83,333.33/month). This even gives you the flexibility to sell more when needed and stay invested during months when you require less capital.

However, in this case, it would attract capital gains tax at 12.50%. We need to see which is more profitable because dividend income is taxed as per the income bracket—non-taxable for some individuals but taxed at 30% for others.

Therefore, we need to find an equilibrium level that guides investors on whether selling equity shares or relying on dividend income is more beneficial from a tax point of view.

Tax on Capital Gains

We have a portfolio of ₹10 crore and want an income of ₹10 lakh every year. However, even if we sell shares worth ₹10 lakh, the entire amount is not profit.

Let’s assume we have been investing for 20 years at 20% CAGR. This means we originally invested ₹26,08,405. Therefore, on selling ₹10 lakh worth of shares, the profit would be ₹9,73,915. With an exemption of ₹1.25 lakh on LTCG, this figure reduces to ₹8,48,915.

Tax Value = ₹1,06,114

Tax in Dividend Income

Now, if you receive a dividend of ₹10 lakh, the entire amount is included in your income. Such high dividends can be tricky because earning just ₹2 lakh more could push you into a higher tax bracket.

The breakeven occurs at ₹5,55,220. This means the moment you earn more than this amount in a year, dividend income would be taxed more than in the capital gains example. This proves that dividend income cannot always be preferred—it depends on the case.

Equilibrium Table

Let’s create a table showing at what level of dividend income the equilibrium tax bracket exists. This means if your tax bracket is higher than the equilibrium level, capital gains are more beneficial. If your tax bracket is lower, dividend income is more preferable.

| Income Required | Capital Gain (81.25 Deduction) | Capital Gain Tax | Equilibrium Tax Level |

| 1,00,000 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1,50,000 | 25,000 | 3,125 | 2.08% |

| 2,00,000 | 75,000 | 9,375 | 4.69% |

| 2,50,000 | 1,25,000 | 15,625 | 6.25% |

| 3,00,000 | 1,75,000 | 21,875 | 7.29% |

| 3,50,000 | 2,25,000 | 28,125 | 8.04% |

| 4,00,000 | 2,75,000 | 34,375 | 8.59% |

| 4,50,000 | 3,25,000 | 40,625 | 9.03% |

| 5,00,000 | 3,75,000 | 46,875 | 9.38% |

| 6,00,000 | 4,75,000 | 59,375 | 9.90% |

| 7,00,000 | 5,75,000 | 71,875 | 10.27% |

| 8,00,000 | 6,75,000 | 84,375 | 10.55% |

| 9,00,000 | 7,75,000 | 96,875 | 10.76% |

| 10,00,000 | 8,75,000 | 1,09,375 | 10.94% |

| 15,00,000 | 13,75,000 | 1,71,875 | 11.46% |

| 20,00,000 | 18,75,000 | 2,34,375 | 11.72% |

| 25,00,000 | 23,75,000 | 2,96,875 | 11.88% |

| 50,00,000 | 48,75,000 | 6,09,375 | 12.19% |

For example, with a ₹5 lakh income:

The taxable LTCG would be ₹3.75 lakh (assuming the entire sale value of equity stocks or mutual funds was gain), attracting a tax liability of ₹48,875—9.38% of ₹5 lakh.

If your income tax bracket is below 9.38%, dividend income would have a lower tax liability. If your tax bracket is higher, capital gains would be more tax-efficient.

Case 1: Tax Bracket 0%, Tax (Dividend) = ₹0 < ₹48,875 = Tax (LTCG)

Case 2: Tax Bracket 20%, Tax (Dividend) = ₹1,00,000 > ₹48,875 = Tax (LTCG)

Thus, we need to plan beforehand whether we prefer dividend income or growth stocks while systematically selling shares. It doesn’t hamper growth because the share price of high-dividend-yield stocks typically falls by the amount of dividend per share paid—similar to selling shares—since the market value of your stocks reduces by the dividend amount received.

Conclusion

While dividends offer predictable cash flows, they aren’t always the most efficient path to wealth creation. Growth-focused stocks, by reinvesting profits, often generate superior long-term returns through compounding. For larger portfolios, systematic withdrawals can mimic dividend income with added flexibility and potential tax efficiency. The choice between dividends and growth depends on your financial goals, tax bracket, and comfort with market fluctuations. A balanced approach—combining high-yield and growth stocks—can provide both stability and appreciation, aligning your portfolio with future cash flow needs and optimal tax outcomes.

Sources:

Leave a comment